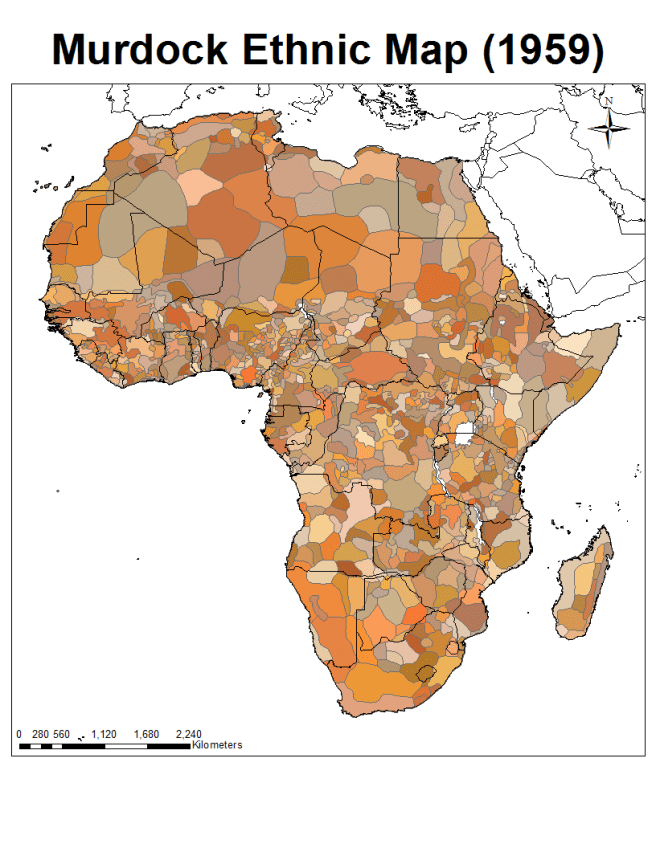

African Unity is Inter-ethnic (not Inter-national) in nature. Unlearn Africa. Learn Africa. Know the tribes and ethnic groups, their languages, histories, cultures, sentiments, traditional friends and enemies. Then you will suddenly see the real Africa and the real African boundaries and borders. They are very different from what was left behind by colonialism. Still unresolved.

African peoples and ethnic units, the real ones, not the national mirages. Any African countries that scrap their tribal languages are taking a lazy defeated step backward, not forward; suppressing forces that will still break out one day again – with even greater force. You can not deny Ethnicity in Africa.

But it does not have to divide us. On the contrary: the acknowledgment and knowledge of it helps us to form natural bridges across ethnic lines. This leads to more – and true, natural – peace and understanding. On the other hand, ignoring it has led to us over and again walking blindfolded and naively into pogroms, genocides, wars at worst – or just never-ending fractures at best.

However, in our need to find peace we have often taken the self-destructive path of sand-papering all our ethnic identities away in order to reduce us all into one amorphous history-less post-colonial European-speaking being. But we thereby go backwards, or sideways, not forwards. We lose, in the illusion of gaining. You have to know your tribe and your fellow African’s tribe; and allow the ethnic part of you to forge ties and forms of understanding with the ethnic part of them. Because our ethnic identities is what we on our own developed for ourselves over the course of millennia. They are not just surface-identities and nothing. Our colonial identities, however, were imposed on us and still sit on us like ill-fitting clothes.

It is ironic that when we associate with non-Africans, we make room for differences based on race and ethnicity. We acknowledge their race and take it into account in the bridge we build between us and them. This then smooths the way to a firm relationship and makes it easy for the shared humanity in us and them to link up with each other. But when we progressive Africans are associating with our fellow Africans, we carelessly believe the colonial white-wash of the irrelevance of our original ancient ethnic identities, and we try to build a relationship on an illusory foundation within which we have not yet reciprocally understood and arranged our minor but important ethnic differences according to their natures. But: Once done, harmonisation becomes very easy and in fact inevitable.

One of the reasons why Igbos and Yorubas, for example, quarrel so much and seemingly find it so difficult to unite politically is that they each keep on expecting the other, unconsciously, to be like them. To be the same end-product of colonialism. To be another version of themselves across the Niger. Especially politically. But since this is not the case, they CRITISIZE that which is different in the other. However only when they have have acknowledged and accepted not only the differences, but the fact that it is natural and complimentary to be different, will they – upon then understanding how to harmonise those differences – begin to see their vast Similarities too.

Despite being the victims of the same conditions all over Africa – corruption, mismanagement, abuse-of-power, and indiscipline – yet we find it difficult to form a strong fist to punch against these situations; and we don’t know why, although the answer is staring us in the face and we are living it everyday. We bunch ourselves into our ethnic groups and then say that tribalism is the problem. But tribalism is not the problem, because most people will always be true to their ethnic identity. It is natural. The problem is that the template for African Unity was created by non-Africans for economic purposes – today we call these templates “African Countries” and they are the member states of the so-called AU (formerly called OAU).

However we Africans need to create alternative theaters and templates of unification and conflict-resolution where the ORIGINAL African identities (today called ethnic groups or tribal families) can themselves work out the rules of engagement or disengagement. Then they can do away with Tribal or Ethnic BIAS. Denying this fact will change nothing, as the Realpolitik in Africa will nevertheless calmly continue to run along those lines and be powered by those forces. Thus, there needs to be a theatre and a dynamic where and whereby this reality can interact with itself and sort itself out.

That is what is still missing: an African self-made Inter-Ethnic OAU. An AU of the original ethnic families. Because the truth is this: the different constituent parts of it are already there. Look at Nigeria: Biafra, Arewa, Oduduwa, Bini Cosmos, Middle Belt. Some even extending naturally beyond the borders of Nigeria. They are all there, the true power blocs and centers of force; the true African identities of the Africans living there. Their FIRST socio-political and cultural identity. Nigeria is in this regard only their second identity. But as long as the first identities find no platform to engage according to homogeneity and share power equitably, the second identity will also know no peace and will remain unstable.

– Che Chidi Chukwumerije