Well, there I was, trapped in a plane on a long-distance flight again and wondering what to do with my time. Tired of watching movies, too wired up to read, and having nothing to write about, I tuned into Lufthansa Radio and all of a sudden, I thought: It’s a whirlwind! But… thank goodness, no, it’s really A Side Order Of Hijiki – and how on earth this is supposed to push the world away beats me. It certainly startles the world though, and pushes away every distraction, making me listen up to what follows next on the album. The silence after track one is short but deafening.

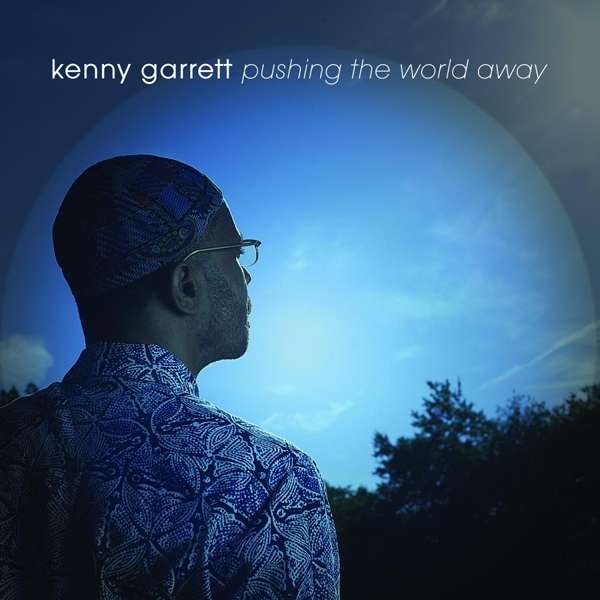

Do I hear John Coltrane in what comes next? I know Kenny Garrett got his start with the Duke Ellington Orchestra and for a while played with Miles Davis. Yet I hear so strong Coltrane in his strains, his lines. Or maybe it’s a way of life, a line of thinking, a point of view and a time in history that walks the streets of similar minds. It’s a pleasure listening to Kenny Garrett’s latest album “Pushing The World Away” (2013, Mack Avenue Records). When the music weeps, it weeps for you. You don’t need to shed the tears yourself. Just listen to them. But then I realised that that was just track two, Hey, Chick.

And then the third track hit the needle. Chucho’s Mambo. A lending from Bossanova, a borrowing from cha cha, kissing latin with a jazzy tongue, mambo all the way. The first section is a happy arriving at an occasion where a chatty hornsman in talkative mood takes over the second part of the music. Now, finally, I hear the brotherhood to Miles Davis. Until, as the song moves towards its final movement, Garrett once again lets the latin rhythms take over and ride you to the end.

There is something, not sentimental, more like reflective, about the fourth track, Lincoln Center, when it starts. The straight-flying horn section pulls you down into the listening, thinking, seat, readying you to pay attention to the piano’s soliloquy that follows. When the solo horn – an alto sax that sounds like it just wants to be alone – follows through, is it anger or upset we hear? What’s paining him? Memories from the past?

Africa here we come in track five – J’ouvert (Homage to Sonny Rollins). Hey. Africa found a home in the Caribbean and then reinvented herself. And if Rollins heard it, Garrett’s heard it too. Sometimes things need to change in order to stay the same. The interplay of tropical horns, thumping bass, clapping hands, the subtlest of jazz, and a trumpet that has not forgotten where it came from, this defines happy intoxication. You hear it here, like a lingering memory that keeps on rebirthing itself.

Track six. That’s It. It’s smooth rhythmic jazz, lightly reminiscent of the class of Coltrane’s Equinox. But only in a different way. In all its melodious pleasuring, it retains its own unique identity..

Kenny Garrett starts track seven like a moon that went on a walk and marvelled at the beauty of the world. Little wonder that his thoughts go up to its Creator, and he titles the song I Say A Little Prayer. Sit back and let him play you the melody of what his heart saw. But it’s no ordinary moon, it’s a saxophone.

Track eight finally got the album title right. Pushing The World Away is in five-four time and fails not to produce the near metaphysical effect of this complex time signatory jazz. The conversation between sop sax and drums, cheered on and temporarily interrupted by the nodding piano right behind them, drives the piece from its first notes. Now agreeing with, now dissenting against each other, they hurry the heady piece along to its distant end. A curiousum about this piece are the alien-like native voices that pray additional harmonies into this strange song. If this doesn’t push the world away, nothing will. But when the world’s away, maybe the light will play.

Piano and Sax promise contemplation on track nine, Homma San. In truth, they promise romance, yearning for fulfilment, far away from the world. Then it comes, the voice of yearning, a sole female moaner, and the effect is complete. The alto saxophone tells the rest of the story, in retrospect.

No, track nine was not contemplation; track ten – Brother Brown – is. Definitely. Sombre is the piano, but not as sombre as the horn dragging his sorrows along in the background. This is only the beginning, tenderly brushed by a very understanding drummer. Go deeper. The mellow mood that began a track earlier is continued here. And does Brother Brown not just make you think of Louis Armstrong?

Alpha Man, track eleven, picks up the pace again. The sax hits the ground running and you get the feeling that you just have to hurriedly follow, anxious to know where he is going, whipped on by the hi-hat.

Rotation makes a nice lively end to this astonishingly lovely jazz album. No wonder this album got a grammy nomination. Seamless blend of tradition and innovation, birthed less than two years ago, and yet this sounds like 2015 and 1950 all at the same time and all shades of blue in between. Bravo, Kenny Garrett! This album is as good on air as it is in print, and definitely worth recommending.

But of course as my luck likes to have it, I always discover the nice things just before they’re over. And just as I am writing these last words while listening to the final notes of Rotation, the plane has landed and the entertainment programme was just been turned off, pushing the world right back where it was before. But the memory of the music, it shall linger…

– Che Chidi Chukwumerije.